Hidden in plain sight, Part 1

Reasons I think JFK's murder was a conspiracy - Introduction

What is the truth, and where did it go?

Ask Oswald and Ruby, they oughta know

"Shut your mouth," said a wise old owl

Business is business, and it's a murder most foul“Murder Most Foul”, Bob Dylan, 2020

Sixty years on, you’d think JFK anniversaries would have taken on the same kind of feel as other long-ago big events, like Pearl Harbor — still generating interest but with virtually everything worth knowing about it revealed long ago, passed into legend. But as evidenced by recent revelations about the infamous “magic bullet” by a former Secret Service agent, and the fact that the US government still inexcusably refuses to declassify thousands of pages of documents and redactions about the event, the assassination remains an evolving, perplexing enigma.

I have a couple of minor personal connections to the event that helped fuel my interest in it from a young age. My grandfather was part of Kennedy’s security detail the last night he was alive, at the Hotel Texas in downtown Fort Worth. I have a copy of a contemporary floor plan of the hotel’s grand ballroom sent to me by someone in the Fort Worth Police Department more than 20 years ago. “X”s are marked on the plan in ballpoint pen indicating where various officers were to be stationed in the overnight hours while the Kennedys slept. They would be there until the completion of a breakfast speech the president was to give the next morning to more than 500 guests. It would be Kennedy’s last speech. On the floorplan, “F. W. Gilmore” is written in neat cursive script next to a set of doors. The “F” stood for Floyd, my middle name. Having had no male offspring, I, his oldest grandchild, am his namesake.

The police uniform 39-year-old Floyd Gilmore wore for the occasion was not his usual work attire. He was a plainclothes officer most of his career. Having been too young to remember him in uniform in his early career, Thursday, November 21, 1963 is the only time my mother, then 13, remembers him actually looking like a policeman, dressed up to leave for duty at the hotel.

Officer Gilmore’s shift took him through the night and into Friday morning. He was there for JFK’s appearance before an enthusiastic crowd gathered in a light drizzle outside the hotel, and then back inside for the big breakfast speech. There, the First Lady joined the president. She wore a dazzling pink outfit with pillbox hat that would become tragically iconic, and bloodstained, in a matter of hours. Receiving a Stetson hat as a gift from the Chamber of Commerce, the president sheepishly declined to wear it, reluctant to be photographed in a hat. When some in the crowd good-naturedly prodded him, he joked that if they would come to the White House the next Monday, he would put it on there.

Before heading home to catch some sleep, my grandfather asked the Secret Service if he could sit in the president’s chair. It was a black leather one with brass casters, specially made to address his back problems. It traveled with him on trips. They said yes, and he did. He may have been the last person to sit in this chair before Kennedy’s death. It was loaded onto a truck for the 30-mile trip to Dallas immediately after. Photos exist of it sitting empty at the Dallas Trade Mart moments after stunned guests were informed the president would never arrive.

My second personal connection to the assassination involved my mother. As a junior in high school, around 1967, she had a job at the Fort Worth branch of a credit bureau. Potential creditors would contact the agency for reports on the credit history of their applicants and people like my mother would look up this information on cards indexed by name. One day, by chance, she came across the envelope for Lee Oswald, the longtime Fort Worth resident alleged to have been the president’s lone assassin four years earlier. He now resided in the city’s Rose Hill Cemetery. That same year, thieves stole his original headstone.

My mother recalls looking at Oswald’s credit report out of curiosity, finding only two inquiries listed, both by law enforcement agencies. One was by the state police, but the other, dated shortly before the assassination, was by the FBI. While intriguing, this in itself is not a bombshell or something terribly surprising. Even in 1967 it was known that the FBI had interviewed Oswald on at least a couple of occasions in 1962 following his return from the Soviet Union to the United States. At the time, though, the FBI claimed it had closed their file on him in 1962. Later, it was revealed that their interest in Oswald continued right up to the assassination and was much more extensive than originally revealed.

When my mother first told me this anecdote as a teenager, at a time when I was engrossed in a newly released documentary series about the assassination, I was amazed and motivated to consume as much conspiracy material as I could find in the pre-internet era. By the time I reached my early 20s, though, under the influence of a highly publicized anti-conspiracy book by journalist Gerald Posner called Case Closed: Lee Harvey Oswald and the Assassination of JFK, I had mentally closed the door on a conspiracy and concluded that the official story must be correct.

Only in the last ten years have I revisited the topic with fresh eyes, new books, and the rich trove of information available online. In doing so, I completely reversed my prior conclusions. I realized that Posner’s 1993 book had deceived me. In my youth and inexperience, I had taken its prolific footnoting and engaging storytelling as evidence of the soundness of its assertions. Now, I realized that the vast majority of its sourcing was from the highly problematic Warren Commission Report, which itself was largely a repackaging of the highly problematic findings of J. Edgar Hoover’s corrupt FBI. Much of what had been released in the ensuing years had either invalidated it or seriously called it into question.

My conclusions today are essentially this: that Kennedy was murdered in a conspiracy primarily directed by a group of insiders from the CIA and other elements of the national security state, as well as Lyndon Johnson, the plot’s most direct beneficiary. I believe others were involved from the world of organized crime, which was already being leveraged by the CIA in their efforts to overthrow Cuba’s Fidel Castro, from CIA-sponsored anti-Castro Cuban dissident groups, and from certain right-wing Texas oil barons. Some other government officials, including a few elected ones, probably had prior knowledge.

It is relatively uncontroversial today to state that Kennedy faced intense hostility from elements of the government he led and from certain groups in the country. Though he was a decorated US Navy veteran, having been wounded and almost killed in World War II, Kennedy was viewed by some in the military and intelligence ranks as a traitor and a threat to national security. And this was in a period when the struggle with the nuclear-armed Soviet Union was at it zenith, considered life-or-death.

While largely aligned with the nation’s military leadership on Vietnam and the wider confrontation with the Soviets early in his presidency, the young Kennedy began making enemies early. The biggest minefields were his handling of the CIA’s failed anti-Castro Bay of Pigs operation in 1961 and the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962, as well as his later efforts at detente with the Soviets that might have ended the Cold War 25 years earlier. All of this combined to cause outright hatred of him among some of the more reactionary elements in positions of power. His policy directive, delivered in the last months of his life, to begin staged withdrawals of American troops from Vietnam at a time when the military and arms manufacturers wanted to wade deeper into the gathering quagmire could not have helped his standing with the reactionaries.

He tried to heed the warnings of his predecessor Dwight Eisenhower about the danger the military industrial complex posed to civilian government. A failed coup attempt by a group of right-wing military generals against French president Charles de Gaulle in 1961 had brought the danger into sharp focus. Intimate profiles sourced from people in his inner circle reveal he was aware of the danger posed by his occasional standoffs with the Joint Chiefs and the CIA — about their desire to escalate in Vietnam, about their desire to invade Cuba (using false-flag events as a pretext), and about their willingness to consider a preemptive nuclear strike on the Soviets. He tried to pick his battles but was stoic about the possibility of it leading to his death. Still, he reportedly remarked to an Administration official that after reelection in ‘64 he wanted to “splinter the CIA in a thousand pieces and scatter it to the winds.”

Likewise, some top organized crime figures hated JFK and his brother Robert, the Attorney General, for the betrayal they felt at the latter’s high-profile mob-busting campaigns. They had worked to help get JFK elected in 1960, allegedly at the behest of his father, a former businessman and American ambassador who had connections in the mafia. And many Cuban exiles involved in the various CIA operations to overthrow Castro blamed Kennedy for the failure of the Bay of Pigs invasion, which resulted in hundreds of their compatriots getting killed or wounded on the battlefield.

For his part, Lyndon Johnson hated the Kennedy brothers for all kinds of personal reasons. They represented an inherited, pampered East Coast wealth that he despised, having worked his way up from poverty in south Texas. He thought they condescended to him behind his back. They had been an obstacle to his political rise in 1960, and they were likely very close to dumping him from the ticket in ‘64 due in part to a brewing influence-peddling scandal from LBJ’s time in the Senate.

That’s quite a collection of groups, but I disagree with those who say conspiracies involving lots of people are impossible because people can’t keep secrets. For one thing, conspiracies rarely require that all involved have full knowledge of what’s going on. Operations can often be compartmentalized so that individuals know only what they need to know to perform their particular functions, without seeing the big picture. Throughout its history, the CIA, for example, has routinely operated according to this principle.

Secondly, if there’s anything recent history should have taught us it’s that our society doesn’t generally reward individuals who speak out against government officials and policies. The use of the phrase “conspiracy theorist” as a derogatory label rather than a neutral, descriptive term seems to have emerged around the 1980s or 90s when interest in alternative assassination theories reignited. It has since become ubiquitous as a weapon against dissenters.

Power structures usually discredit or retaliate against people who illuminate truths they want kept in the dark. And there is no bigger power structure than the U.S. government. Courageous people with inside access, or people on their deathbeds with nothing left to lose, sometimes do speak out about government secrets, even about the JFK assassination. But when they do, they’re discredited or ignored. In a “he said, she said” scenario, the vast majority of people will believe the polished words of government officials and their media mouthpieces over some individual portrayed as unhinged for speaking out.

And it’s not difficult for the government and media to turn credible witnesses into crackpots in the public’s mind. For examples one only has to look to the front-line physicians, cardiologists, and other qualified medical personnel demonized during Covid for speaking out about successful treatment protocols or about the dangers of inadequately tested Covid vaccines. Previously considered respected members of their profession, many were fired, had their contracts terminated, or lost their licenses for threatening Pharma profits. Each time that succeeds against another brave whistleblower, many others choose to self-censor, creating a ratcheting cycle of cover-up.

For those who seek with open minds and patience, though, illuminating facts eventually trickle out. In subsequent installments of this series, I’ll provide a high-level overview of some of those facts that, when considered as a whole, have led me to conclude that JFK was killed in a conspiracy directed by disaffected elements of his own national security apparatus. It was likely not some officially sanctioned project that would show up in documents but a clandestine effort “off the books”. In later posts I may focus and go into more detail on some of the more interesting aspects I address in this series.

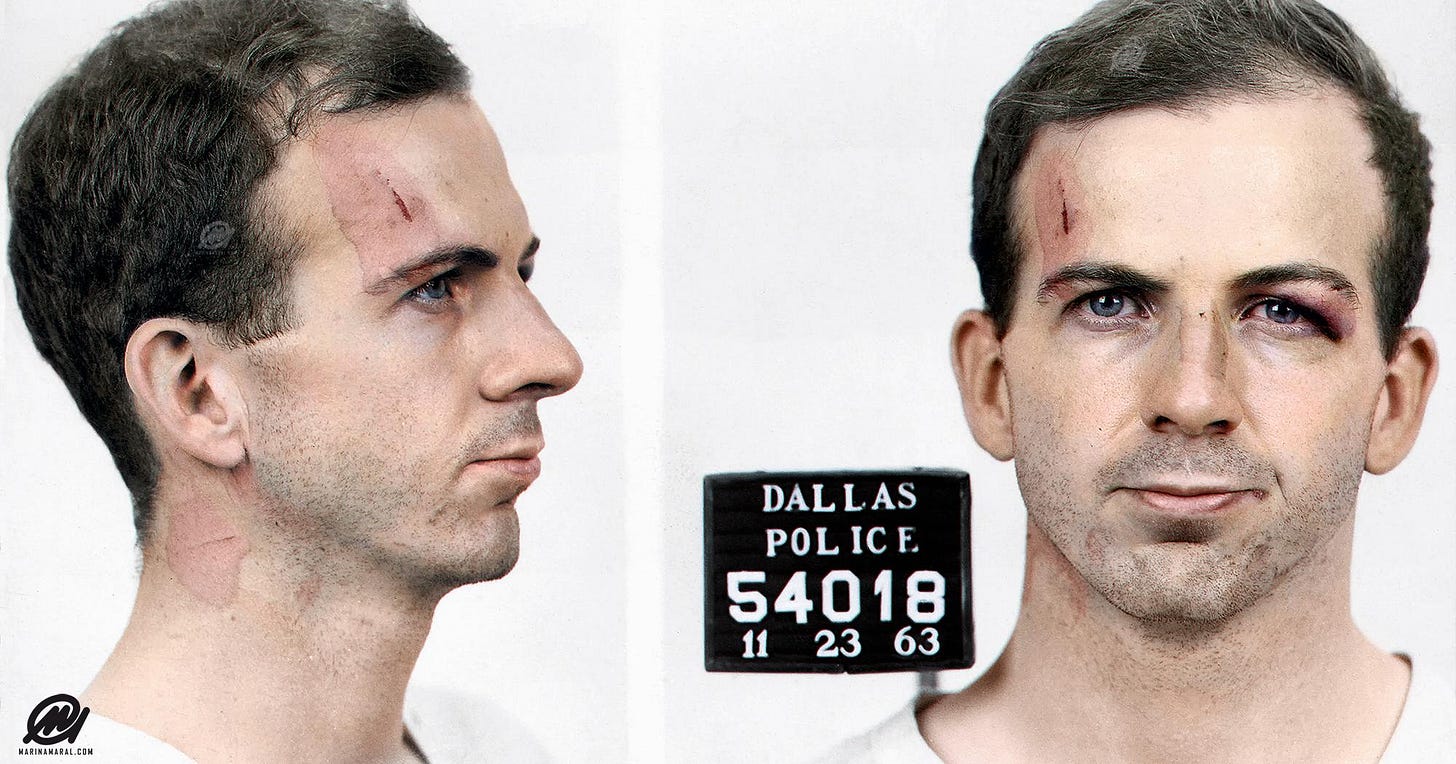

On the pivotal question of whether I think Lee Oswald killed JFK, either acting alone or in concert with others, I’ll give the best answer I can: I think he was undoubtedly involved in the plot to kill Kennedy in some capacity. It’s pretty clear to me that he’d been a tool of American intelligence since his Soviet defection, which I believe was a false defection. But whether he actually pulled a trigger on November 22, I don’t know. If he did, I don’t think he was the only one and I seriously doubt that any shots he fired were the fatal head shot that killed the president. I definitely think he was shocked and unprepared to find himself in custody as the sole fall guy for Kennedy’s murder. I think he was telling the truth, or some semblance of it, when he exclaimed while being dragged by officers through a jail corridor 36 hours before his own sensational murder, “I’m just a patsy”.

We’ll do well to remember that Oswald was never convicted of anything. The conclusions of a presidential commission of officials hand-picked by the chief beneficiary of the crime is no substitute for a full adversarial trial by jury. In a trial, witnesses are sworn under penalty of perjury to speak the truth and the innocence of the accused must be presumed until his guilt is proven beyond a reasonable doubt. The least we can do in this regard is to resist the increasingly common practice of dropping the word “alleged” when referring to Oswald as Kennedy’s assassin.

It is now accepted history that the CIA sponsored coups to overthrow governments almost from the moment of its inception in 1947 and likely continues to do so. In just the first 30 years of its existence, the list included: Iran in 1953, Guatemala in 1954, Indonesia in 1958 (failed), Congo in 1960, Cuba in 1961 (failed), the Dominican Republic in 1961, Iraq in 1963, South Vietnam in 1963, Brazil in 1964, and Chile in 1973. But I think this list is incomplete without another entry, the biggest one of them all: the United States in 1963.

Richie Graham is based in Little Rock Arkansas USA and writes from a free-market libertarian, anti-interventionist perspective.