The trouble with Persia

Donald Trump thought he could browbeat Iran into submission with his repudiation of the nuclear deal. He somehow got it into his head that the country received a sweetheart deal that took advantage economically of the United States – one of his chief concerns affecting other areas of his foreign and trade policies. He apparently didn’t understand that the money Iran received consisted of their own previously frozen funds. It had been sitting in banks for more than two decades collecting interest since Iran’s payment under unfulfilled arms contracts prior to the imposition of sanctions.

The Iranians, long used to pressure from the West, have refused to buckle, and have incrementally increased their enrichment of nuclear material to put pressure on European countries still nominally part of the agreement. Those countries remain in the deal in name only, fearful of U.S. reprisals if they meet their commitments to Iran under the agreement to increase investment. This antagonistic stalemate, interspersed with tit-for-tat incidents of ship-seizing, drone-downing, and acts of sabotage in the Persian Gulf region of dubious origins, pinned by the West on Iran, follows a long pattern of Iranian-Western relations.

Most Americans over a certain age think of Iran primarily through the lens of the 1979 Islamic Revolution and the subsequent taking of 52 American hostages for 444 days, ending with the hostages' release to great fanfare precisely upon the inauguration of Ronald Reagan as president. This unambiguous “fuck you” to Jimmy Carter did little to raise the country’s standing among Americans. Since then, Americans’ views of Iran have never breached the 20% favorability mark, according to Gallup. Iranians don’t care much for us either, and, as one would expect, Trump’s actions have propelled that disdain to new levels.

The official line in the US is that Iran is a terrorist state, owing mostly to the country’s support for the Lebanese political and paramilitary group Hezbollah, considered a terrorist organization by most Western-aligned governments. Hezbollah has been accused of carrying out such bloody attacks as the 1983 Beirut barracks bombing in Lebanon that killed 241 US Marines and 58 French paratroopers, and the 1996 Khobar Towers bombing in Saudi Arabia that killed 19 US servicemen. Iran has disputed some of these claims.

Regardless of Iran’s disputed culpability in the attacks attributed to Hezbollah and its predecessors, there’s no doubt about the infamous hostage-taking and the stain it placed on Iran in the minds of Americans. That event and the ascendancy of the ayatollahs has done more than anything else to cement the image of Iran as being a state ruled by ultra-radical Islamic fundamentalists and an enemy of America. But history didn’t start in 1979. Iranians are a proud people with a long and distinctive past, and they have good reason to distrust, if not outright hate, America.

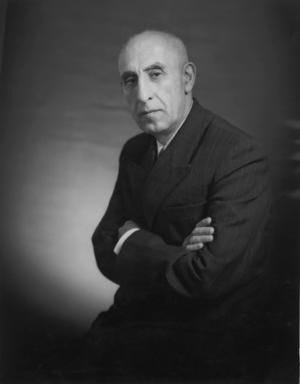

America’s modern-day involvement in Iran began in the 1950s when Britain enlisted the support of the US for the overthrow of a charismatic and popular Iranian leader named Mohammad Mosaddegh. This is described in vivid detail in Stephen Kinzer’s “All the Shah’s Men: An American Coup and the Roots of Middle East Terror”. Mosaddegh had become prime minister of Iran in 1951 and quickly set about instituting reforms and increasing the power of the democratically elected parliament at the expense of the Shah, the title given to kings in Iran for centuries. His most controversial move, at least outside of Iran, was nationalizing the British-owned petroleum monopoly the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (now part of BP), which paid Iran only a small fraction of the revenues it received from Iranian oil.

Britain was enraged, and after making little headway with Harry Truman’s administration, they convinced the newly installed, more aggressive Eisenhower boys that Mosaddegh was pro-communist. That was enough. The CIA, along with British intelligence, initiated Project Ajax in August 1953, led by Teddy Roosevelt’s grandson Kermit, to overthrow Mosaddegh and vest essentially dictatorial powers in the Shah. The Shah went on to enjoy a 25-year reign that protected Western interests and brutalized noncompliant Iranians until the 1979 Islamic Revolution swept him from power and instituted the current Islamic Republic. American control of the country ceased, and soon thereafter began a year-long saga of attempts to free the hostages seized from the US embassy in Tehran in November 1979. Jimmy Carter even sent a few military helicopters and a C-130 transport plane into the Iranian desert as part of an abortive rescue attempt. One of the helicopters flew into the plane, crashing and burning, a metaphor for Carter's presidency and 1980 campaign.

A year after the revolution, the US supported Iraq's Saddam Hussein when he initiated his war of aggression against Iran that would last eight years and result in hundreds of thousands killed (but they weren't Americans, so who's counting, right?). Among other material support, the US provided dual-use technology to Iraq and assisted with satellite targeting at a time when they knew Saddam was using chemical weapons against Iran. Tens of thousands of Iranian soldiers and civilians were killed by Iraqi chemical weapons, with the US providing assistance the whole time.

The Tanker War phase of the Iran-Iraq War began in 1984 when Iraq attacked an Iranian oil terminal, hoping Iran would retaliate by closing the Strait of Hormuz and thereby draw the US directly into the fight. Matters gradually escalated to the point that by 1987 Iraq was cut off from access to the Persian Gulf and was relying upon Kuwaiti shipping to export its oil (Iran’s Shia ally Syria had cut off Iraq’s access to a key oil pipeline to the Mediterranean). Iran and Iraq were engaged in tit-for-tat strikes against the other’s shipping and oil facilities. The US responded to Kuwaiti pleas and intervened in July 1987 by sending military force, mostly naval, to the Persian Gulf to protect Kuwaiti shipping that had been re-flagged as American in order to permit military escorts under US law. That same year, a missile from an Iraqi fighter jet struck the frigate USS Stark, killing 37 sailors and injuring 21 others, an act that Iraq claimed was accidental. The US initially blamed the attack on Iran.

A little over a year later, on July 3, 1988, the guided missile cruiser USS Vincennes fired two surface-to-air missiles at what its crew thought was an attacking Iranian F-14 fighter. One of the missiles struck its target, an Airbus passenger jet operating as Iran Air Flight 655, destroying the plane and killing all 290 aboard, including 66 children. The US initially claimed that the ship was operating in international waters, that the Iranian plane had been descending toward the ship in a provocative manner, that the plane’s radio transmitter was squawking on a military mode rather than civilian, and that the pilots had failed to respond to radio challenges. All but the last of these claims were false. It was later established that the ship was operating in Iranian territorial waters. The Vincennes’ own radar systems recorded that the airliner was climbing at the time and that it was squawking on only the civilian frequency. It was true that the pilots had not responded to challenges but given that the crew of the Vincennes apparently didn’t know the plane was a civilian airliner and wasn’t monitoring civilian frequencies, they didn’t refer to the flight by its callsign. With numerous civilian and military flights operating in the area at once, it’s not surprising that an airline crew would not think that vaguely worded warnings toward an “unidentified Iranian aircraft” flying at a different speed than their instruments indicated were actually directed at them.

It’s hard to overstate the negative effect the Iran Air disaster had on Iranian views toward America, particularly given US government's response to it. The US said Iran shared blame for the incident, stating its regret for the loss of life but never formally admitting wrongdoing. American media, which just five years earlier had condemned the Soviet Union in the starkest terms for the shoot-down of a Korean airliner it believed to be a hostile plane over its territory, now spoke only of the difficulty and complications of operating sophisticated military hardware near a civilian air corridor. George H.W. Bush, running for president at the time, bristled at the very suggestion that the United States should apologize. Later as president he awarded The Vincennes’ captain William Rogers the Legion of Merit. It wasn’t until 1996 that the US settled a case at the International Court of Justice over the downing and agreed to pay over $130 million to Iran, still not formally accepting responsibility. Many Iranians at the time believed the attack was intentional and presaged a more direct US intervention into the war on behalf of Iraq. The US has treated the suspected downing of Malaysia Airlines Flight 17 in Ukraine in 2014 quite differently. The US and its Western allies have accused Russia and ethnic-Russian Ukrainian separatists, on whom they pin the blame for the downing, of war crimes, seeking their criminal prosecution despite strikingly similar fact-patterns between the two incidents.

Perhaps no other aspect of Iran's foreign affairs gives its enemies more ammunition against it than its strident verbal attacks on Israel and the US. The John McCains and Benjamin Netanyahus of the world can always point to a "death to America" reference or calls for the destruction of the state of Israel by an Iranian Supreme Leader. Iran does itself no favors in the wider world with such hateful rhetoric, even if it's popular at home with a public that has great sympathy for the plight of the Palestinians displaced by the creation of the Jewish state and antipathy toward a United States that protects what they view as the aggressor. But compare the rhetoric to Iran's actual conduct. Iran hasn't started a war in its modern history (unless you attribute everything Hezbollah does to Iran). They've abided by the Iran nuclear deal to the letter, at least until the Trump Administration repudiated the deal. And many people don't know this, but Iran is home to as many as 15,000 Jews who have their own schools, synagogues, and even hospitals. In fact, Iran has the largest Jewish population in the Middle East outside of Israel. America’s key Muslim ally in the region, Saudi Arabia, by contrast, has a Jewish population of precisely zero, at least according to official data. When a finger-wagging Mike Huckabee stated in 2015 that the nuclear deal would “take the Israelis and march them to the door of the oven” he was conflating opposition to the state of Israel with the violent antisemitism of the Holocaust. Iranian Jews, among many others, might have something to say about that kind of comparison.

Anyone who thinks the US government chooses to ally with or demonize another country based on the degree to which it shares America's love of democracy and human rights is fooling himself. If that were true, successive American governments would not have considered Saudi Arabia an ally despite its being ruled by a brutal and dictatorial absolute monarchy engaged in aggressive war with its neighbor Yemen. If that were true, Hillary Clinton would not have called longtime Egyptian dictator Hosni Mubarak and his wife "friends of [her] family". Geopolitics is a cynical game. More than anything else it's about power and money. The US has carved out a special place for itself as the preeminent world power. All others must bow to its authority and pay tribute to its oligarchs (see Saudi donations to the Clinton Foundation, Ukrainian enrichment of Hunter Biden). Those that do are rewarded and their misdeeds minimized and rationalized. Those that refuse are demonized and punished. It's as simple as that. Ever since it dared to shrug off the yoke of a quarter century of American domination in 1979, Iran has been in the latter camp. It's up to the next generation of American leaders to choose whether it stays there.

Richie Graham is based in Little Rock Arkansas USA and writes from a free-market libertarian, anti-interventionist perspective.