Third wave problems

Where we stand with Covid, both here and abroad, as the CDC reverses on masks

With the CDC issuing new mask guidance yesterday recommending a return to masking indoors for both vaccinated and unvaccinated, it seems a good time to take stock of where we are in the United States and globally with respect to Covid-19.

Cases and deaths

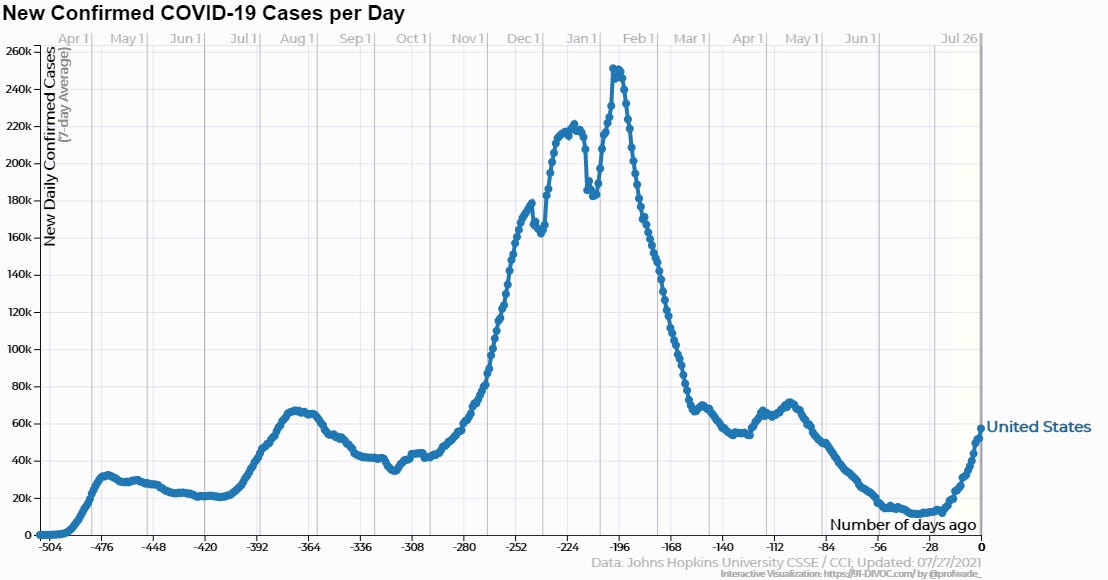

The so-called “second wave” of Covid ended when the United States and many individual states saw a sudden peak and then a sharp, sustained collapse in reported Covid-19 cases beginning around the January 10-15 timeframe. The Pfizer and Moderna mRNA vaccines had been authorized for distribution under FDA “Emergency Use Authorizations” only in mid-December, and as of the peak only around four percent of Americans had received one vaccine dose, with fewer than one percent having been fully vaccinated. It’s difficult then to see how vaccination could have played a significant role in the collapse in cases, at least not in the initial stages.

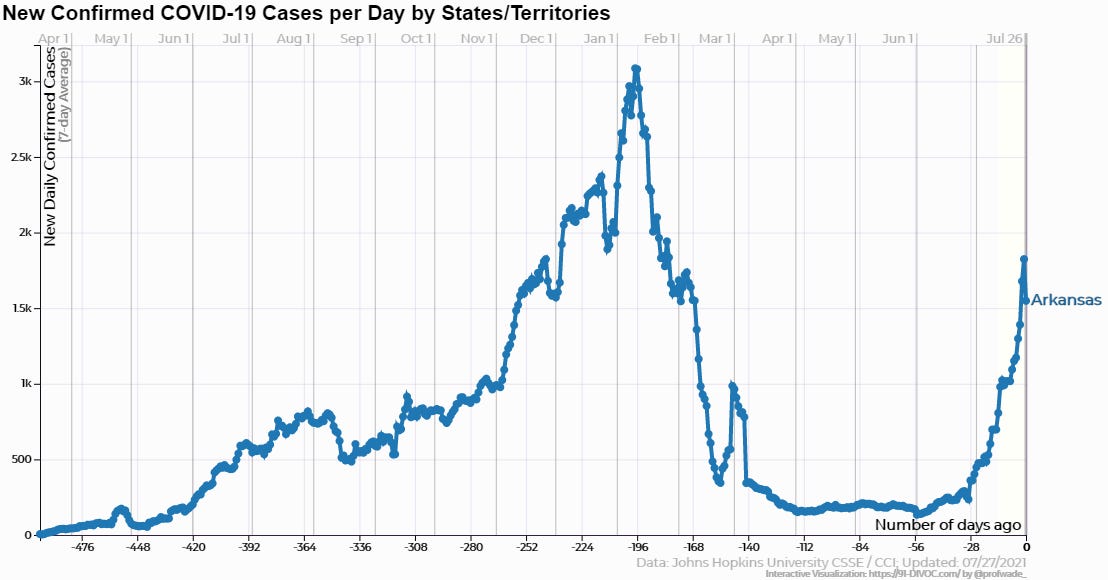

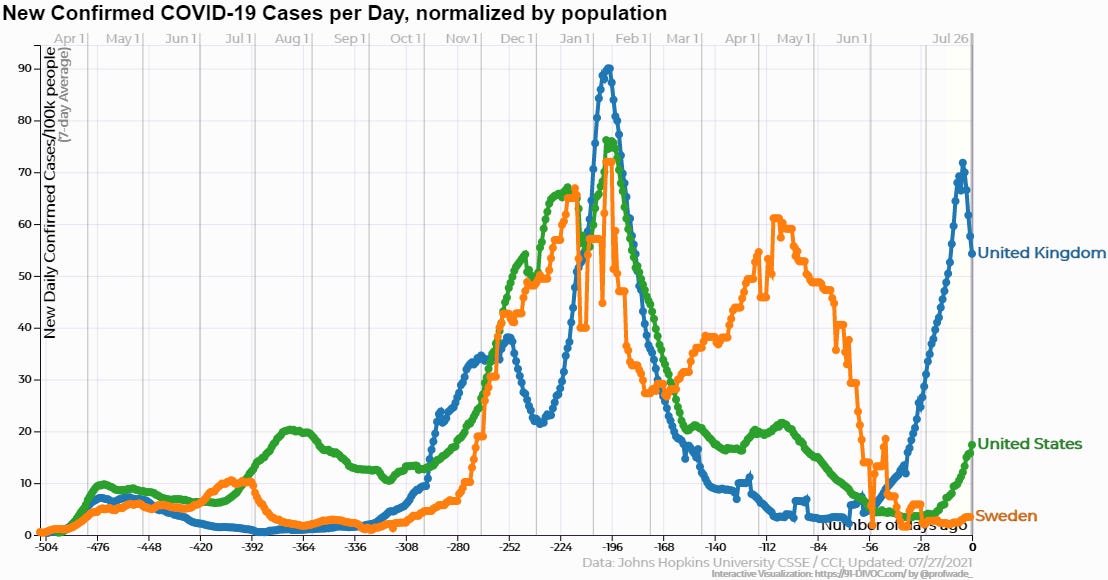

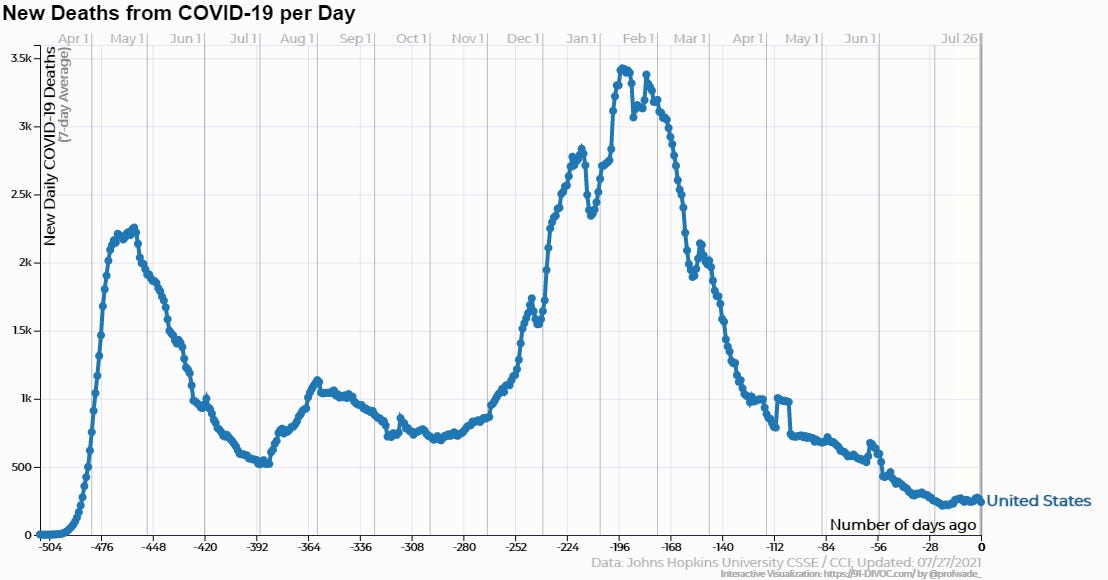

The chart above shows a resurgence in cases in July as the much-feared “Delta variant” of the virus reportedly began to circulate more widely in the US. Deaths attributed to Covid in the same timeframe saw no significant increase in the US as a whole, although certain “hot-spot” states saw jumps.

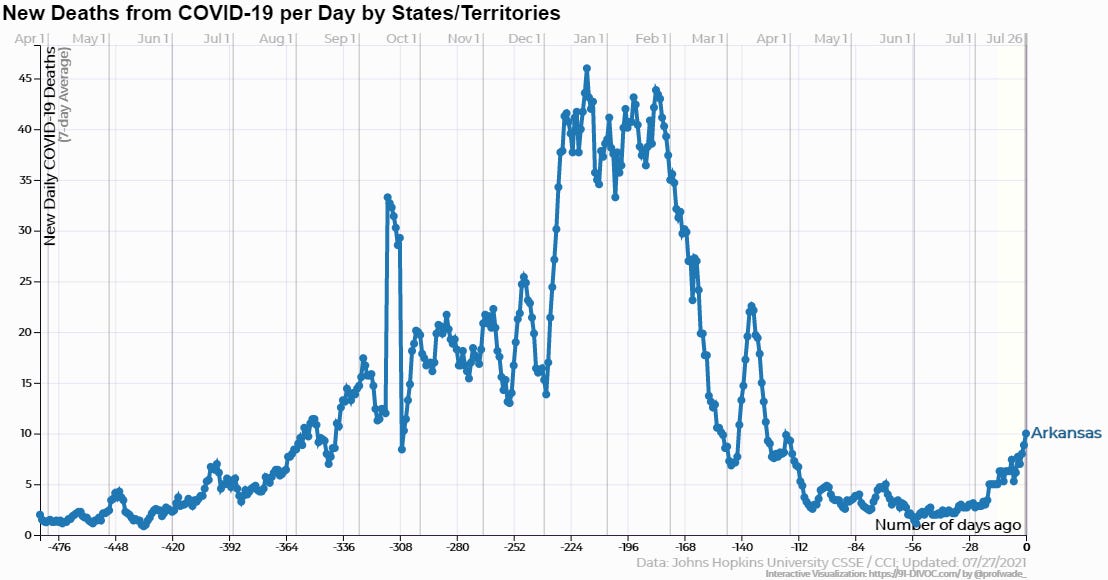

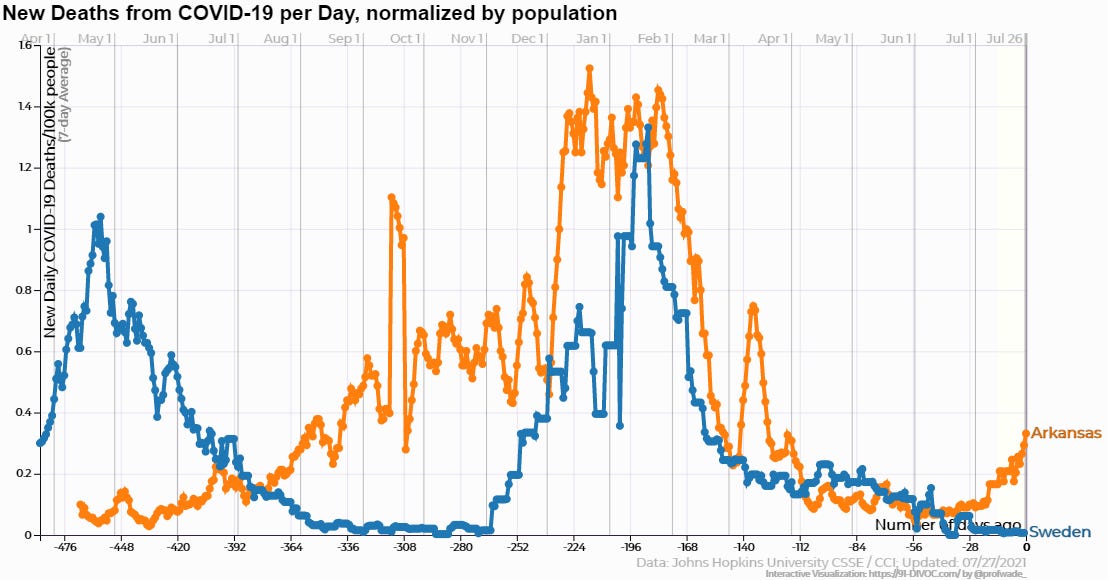

One of the hottest of hot spots is my state of Arkansas, where reported cases are up significantly since June and deaths attributed have been climbing as well. This is widely blamed on the low vaccination rate. As of this writing, according to the Arkansas Department of Health, about 41% of the state’s vaccine-eligible population has been fully immunized, with an additional approximately 11% having had one shot. There’s been a noticeable uptick in vaccinations here recently as government and media have sharply increased alarmist rhetoric.

One example of that was a recent spate of headlines across local media announcing that two Arkansas children had died of Covid, with headlines that implied these were new deaths being caused by the Delta variant. When you read the story you learned that, while one of the two child deaths in Arkansas attributed to Covid had indeed occurred recently, the other was last year, apparently only recently having been confirmed. Of course, any death, and especially one involving a child, is a tragedy for the family and friends affected. But it remains true that of the 600,000 plus Americans whose deaths have been pinned on Covid since the beginning of the outbreak, fewer than 400 were under 18. Children have a statistically higher risk of death from crossing the street. Whether the Delta variant will change that remains to be seen, but there’s no evidence yet that it has.

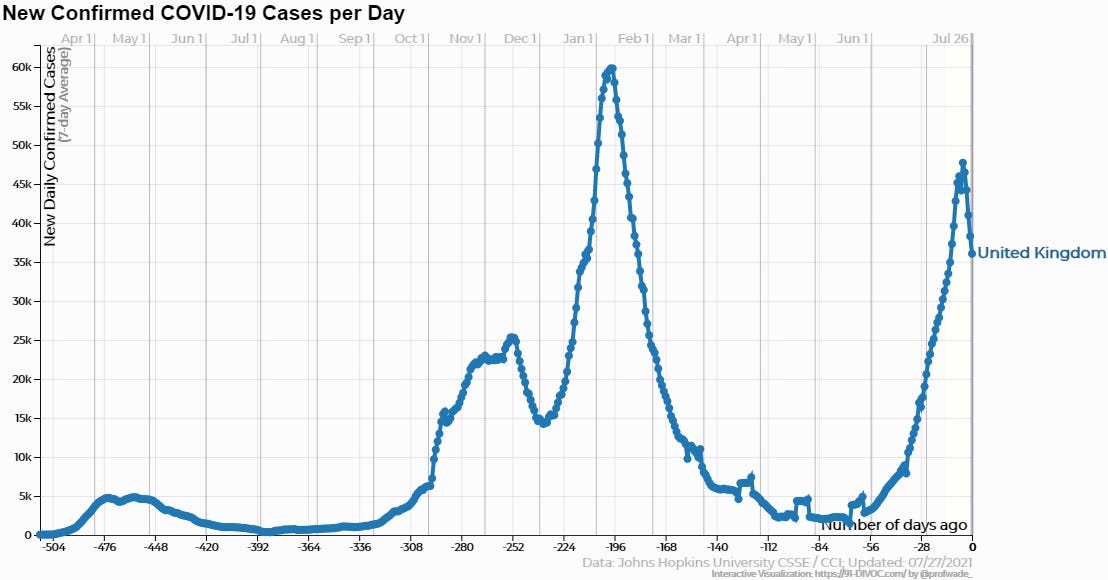

What about the case and death data overseas? Let’s look at one of the countries with the highest vaccination rates first.

With their recently secured independence from the European Union, the British government were eager to highlight the benefits of Brexit by showing how quickly they could get needles into arms without all the Continental red tape. They were the first major western country to authorize a Covid vaccine in early December and have now reached almost 71% of vaccine-eligible people fully immunized, using a combination of Pfizer, Moderna, and their home-grown AstraZeneca vaccine. That significantly exceeds the almost 58% that the CDC says are fully vaxxed in the US, although unlike the US Britain has not yet authorized shots for under-18s.

If you’re a Covid vaccine advocate, the UK is about the best place you can point to make your case. It has a large, dense population, that appears to be more trusting of government than are Americans, and thus more willing to comply with its demands (opinion polling has recently indicated a large percentage of the British public support restrictive Covid measures, even if implemented permanently). Until recently, vaccine advocates would have been disappointed in the number of British cases, which were climbing steeply. But within the last week or two, there’s been a sharp reversal in them.

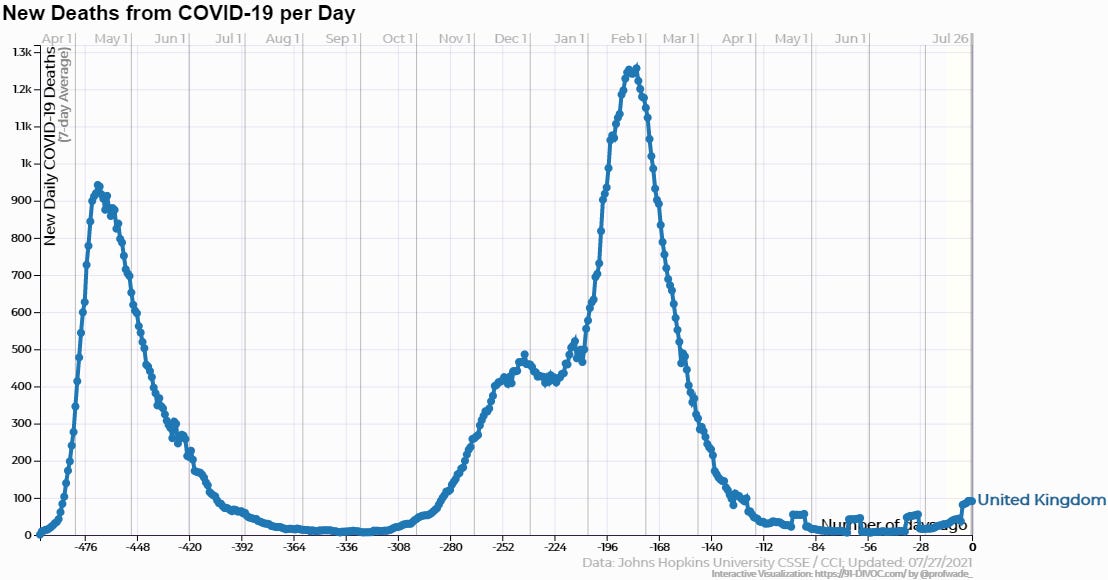

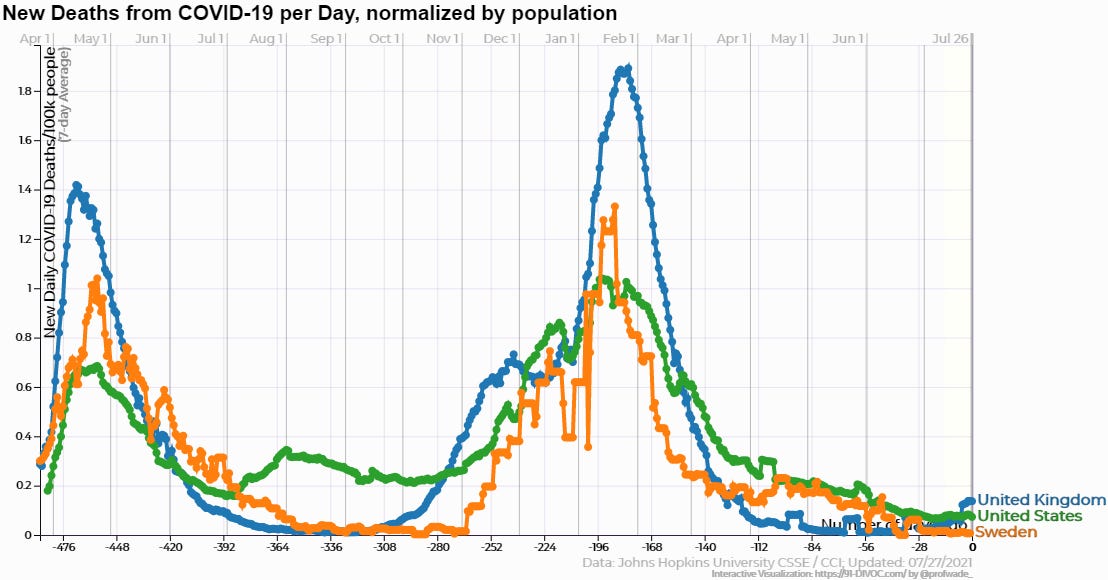

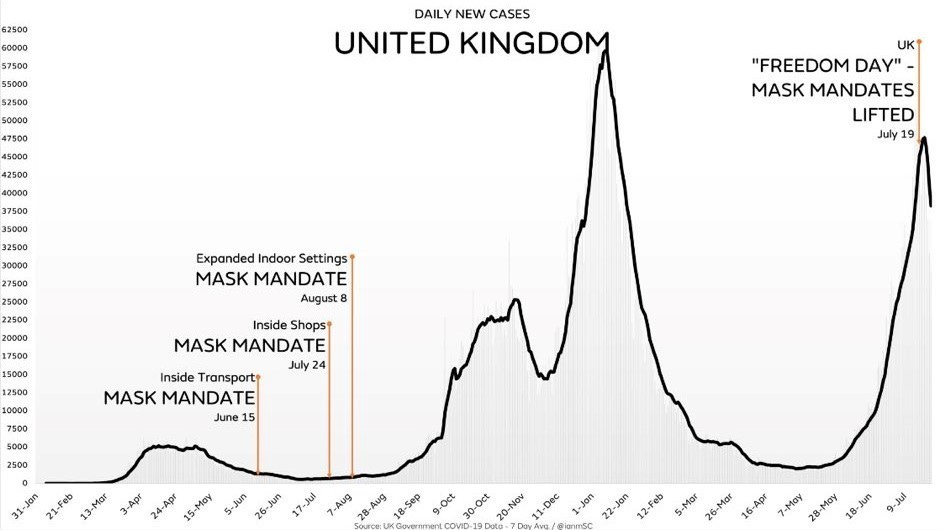

Deaths attributed to Covid in the UK have remained relatively low throughout the second wave. Britain has been one of the strictest states in applying the whole panoply of Covid measures, whether it be mask mandates, lockdowns, or aggressive vaccine distribution and advocacy. Only very recently have the restrictions been loosened (July 19 was widely being referred to as “Freedom Day” there due to the expiration of a number of measures). But since cases were climbing sharply during most of that time while deaths remained muted, it would seem vaccinations would be the most likely measure to credit. If they didn’t do much to prevent spread, maybe they at least reduced disease severity?

The case of Sweden

Sweden has been a favorite of mine since the beginning of the pandemic. I highlighted their light-touch approach last year here and here. The country’s state epidemiologist Anders Tegnell and the public health agency he leads took flak early on for an approach that focused on isolating the most at-risk populations, encouraging social distancing and measures like hand-washing, and essentially allowing the rest of the population to achieve herd immunity naturally. They did enact a ban on large gatherings and closed high schools, although elementary and preschools remained open. As I outlined in my first article on Sweden, based on aggregated Google mobility data, while Swedish traffic to public places did decrease somewhat last summer, the decrease was very minor compared to the total collapse in traffic in Britain as it locked down.

Sweden was soft even on face masks, their public health authorities recognizing that the science was never there to justify their use. They never mandated them, and they recently dropped their half-hearted recommendation that people wear them on public transport. Voluntary mask-wearing in Sweden never took off.

Other countries who imposed restrictive measures on their people of course didn’t like the fact that this Nordic holdout, which had been so often favorably cited by those on the left as a bastion of statism, was making them look bad by mostly leaving people alone rather than disrupting their lives and hyping fear. Every time a blip in the charts showed things might be going south for the Swedes, ominous headlines would appear in the US and Europe intoning about the country’s risky gamble and predicting imminent doom for them. Comparisons were often made to their Nordic neighbors Norway and Denmark, which had lower case numbers and deaths than they, while carefully avoiding comparisons to other countries like Britain and Belgium that were faring much worse with more restrictions. The doom kept getting pushed back as Sweden’s case and death numbers, on a per-capita basis, broadly mirrored those of the rest of Europe and the United States.

Then, starting February of this year, it looked like Sweden’s critics were finally being proven right. Cases began to surge as the second wave was collapsing in the US and UK. But, fortunately, the death numbers, usually a lagging stat, never really took off, and as of now Sweden is faring better than both Britain and America in terms of cases and deaths attributed.

Excuses were never in short supply. The main one seemed to be that Sweden’s population and population density were low and that meant it couldn’t be compared. The country has ten million people, with only 60 people per square mile. But that latter stat is highly skewed by the fact that vast tracts of Sweden’s mountainous north and west are virtually unpopulated. In the places where Swedes actually live, the density is much higher. 85% of Swedes live in urban areas. And if you think they haven’t yet faced the Delta variant, you’d be wrong.

But if the US and Britain are too big to compare to Sweden, let’s compare their outcomes to Arkansas, with a population of three million people and a density more comparable to Sweden. Arkansas was never a bastion of Covid measure compliance, but we did send schoolchildren home, close bars, restaurants, and other venues, and mandate masks in public accommodations, none of which Sweden did. So, how do they compare? After suffering through their initial wave before things had really taken off in Arkansas, quite a bit better. Then around the beginning of this year their death numbers started to mirror us more closely until very recently when Arkansas began taking off again.

So how is Sweden doing in terms of vaccinations, you might ask? Might that be the reason they’re seeing much lower numbers of both cases and deaths now than Arkansas? Well, maybe. Sweden’s latest government statistics show the country’s fully vaccinated are at 49% of the vaccine-eligible population, eight percent higher than Arkansas’ 41%. But they report that an additional 28% have been vaccinated with at least one dose, much higher than the number of Arkansans who have been vaccinated with only one dose.

It’s easy to think of other hypotheses for why Sweden might be doing better as well. Like most Europeans, Swedes live much healthier lives than Arkansans. And their light-touch approach could have exposed more Swedes to the virus and allowed them to develop a greater degree of long-lasting natural immunity. But the most straightforward explanation is that vaccines have played a role, at least in terms of reducing their death rate.

India’s experience

Beginning in April and leading into May, India began its own second-wave surge that captured headlines globally. Their vaccination rate was in the single digits and remains so today. Yet, extraordinarily, they’ve reduced their cases and deaths by 90% since that time. They did so after widespread adoption of the anti-parasitic drug ivermectin, in some cases combined with hydroxychloroquine and other drugs. These drugs have been around a long time and are available generically. For that reason, no pharmaceutical company stands to make tens of billions of dollars from their use as Pfizer and Moderna expect to make from their mRNA vaccines. Because the NIH, CDC, and WHO are captured by the pharmaceutical industry and largely do their bidding, their stance towards use of these long-standing therapeutics to save lives from Covid has been extremely negative, even dismissive. But there are studies that show they work, and the anecdotal accounts of their effectiveness from those treating on the front lines (as opposed to those in charge of doling out research dollars from a nicely appointed office in DC) can’t be ignored. Nor can the circumstantial evidence of the Indian experience.

The masks charade

There may be no aspect of the Covid crisis with which governments have been more disingenuous with the public than that of masks.

There have been few, if any, large-scale studies of masks' effectiveness at preventing community spread of Covid, simply because the condition is so new. Instead, there are water droplet dispersal studies from which a possible effect is inferred. There are numerous studies going back to WWII on masks' effectiveness at preventing community spread of flu. Despite what some meta-analyses of those studies conclude in their summaries, those studies are largely inconclusive.

Some show a small statistically significant effect, some show no effect, and some show an affect only when combined with hand washing. This recent meta analysis is a good example. It concludes mask use "could be beneficial", but when you read the eight clinical trials linked in the study, you find that most were either inconclusive, showed no statistically significant effect, or showed no effect of masking without hand washing.

Then there’s the question of whether masks have any measurable negative effects on the wearer. It’s been a contentious topic with government and media advocates quick to dismiss it as a possibility. But the answer is not cut and dried, and there are trials that show a risk to those susceptible to reduced blood-oxygen levels or increased carbon dioxide. Properly fitting masks create a void in which exhaled CO2 is collected and inhaled. This study out of Spain found that masks decreased the availability of oxygen by 14% and increased CO2 concentration by 20% in those who wore them.

And finally, there's the anecdotal evidence that most countries had their second waves of Covid, and their largest number of cases and deaths attributed to Covid, AFTER mask mandates were imposed.

What masks really represent is a feel-good measure for many people, and a punishment to vaccination resisters for others. They are a virtue signal, a symbol of compliance and submission, and a muzzle to remind you that the state is your master and they have the power to shut you up.

Other unresolved issues

Other problems with the Covid pandemic paradigm identified last year remain unresolved and likely taint the official numbers. These unresolved problems don’t necessarily negate the idea that a pandemic exists, but they call into question the degree to which it exists and whether the numbers have been inflated, either intentionally or inadvertently.

The problem of false positives with overly sensitive PCR tests that I highlighted here and here still exists, although it’s not talked about much. If PCR cycles in most coronavirus tests are still in excess of 35 cycles, then the real possibility exists that, in some cases, a majority of positives are actually false positives, with the test detecting left-over fragments from dead virus contracted during a previous wave of infections. This issue was highlighted in a bombshell New York Times article last year, but many missed its significance.

And the fact that the vast majority of Covid deaths have, on average, three comorbidities and are of advanced age means it may be impossible to know how many cases and deaths were actually people admitted to hospital for, and who died from, something else. With recent reports that more than half of Covid hospitalizations in the UK are patients who only tested positive after admission for some other condition, the real danger that more are being hospitalized with Covid rather than because of Covid remains a real possibility. If that’s happening in Britain, it’s almost certainly happening here as well.

Conclusion

People have a presumption that the scientists and health officials who represent their government are an authoritative source of information. They represent “the science”. Telling them that the science is not clear, that there’s disagreement, and that, for instance, Sweden’s version of Anthony Fauci says very different things than Fauci does can create cognitive dissonance. So people just tune it out. They listen to the authorities that their own media highlight, and of course their media highlight the officials of their own government. Or they rationalize it by treating science like a democracy, where minority voices (as Sweden’s Anders Tegnell certainly is) are simply dismissed because they’re not in the majority — part of the “consensus” in the parlance of science.

But that kind of thinking is seriously flawed. Often in the history of science contrarian viewpoints have proven to be the correct ones over time. Groupthink and confirmation bias are as endemic to science as they are to other forms of human collective behavior. More serious people recognize this, do their own research, and come to their own conclusions after listening to different arguments on important topics. Some don’t have the time or the inclination to do this. They just want someone to tell them what to do. But for those who do wish to take personal responsibility for matters as important as their health decisions, having government treat them like children incapable of discerning what’s best for themselves and their families is a terribly cynical and anti-democratic form of governance.

We don’t (yet) live in a technocracy. Scientists advise. Elected officials decide. And in a healthy constitutional republic based on principles of limited government, they leave most of the decisions to the public themselves, providing them as much unvarnished information as possible with which to make their own decisions. When we surrender these principles to the idea that the world is too dangerous for this level of personal autonomy, we may be sleepwalking into an unknown that will turn out to be far worse than any Covid doomsday scenario they used to frighten you into putting on the shackles and handing them the key.

Richie Graham is based in Little Rock Arkansas USA and writes from a free-market libertarian, anti-interventionist perspective.